100 years ago today, on 24 April 1916, a minority of Irish men and women led an armed insurrection against British rule to gain independence. While the series of events, that are now known as the Easter Rising, were neither the start nor the end on the long path to a free Ireland, they have a very special place in Irish history and the hearts of Irish people all over the world.

Whenever I read something about the younger history of Ireland, I always noticed the particular relevance of the Easter Rising of 1916. And when we were over in Ireland for Christmas and the New Year, I was fascinated by all the different advertisements for the centenary, the commemoration of the Rising’s 100-year anniversary, that already caught my attention at Dublin Airport.

I started to research for this post and was overwhelmed by the amount and variety of information available in Irish media. It is absolutely breathtaking! There also is a vast number of events that guide Ireland through this exceptional year offering numerous opportunities to remember and celebrate the 1916 Rising and its legacy.

Overview

The best and shortest explanation that I came across summarises what the Rising was and what effect it caused.

The Easter Rising took place in Dublin, and a few outposts across the country, between Monday 24 April and Sunday 29 April, 1916. It was a rebellion against British rule in Ireland and was defeated after a swift British military response. As a military campaign the Rising was ultimately a failure but it had an important legacy in that the British response to the event turned the majority of the Irish public away from the idea of Home Rule and towards the concept of a fully independent Irish Republic.

– Professor Mike Cronin

A more visual and more detailed description is provided by the following video.

Situation

By the beginning of the 20th century, England had been embroiled in Ireland for almost 800 years. In the 1910s, the dominant political force was the moderate Irish Parliamentary Party led by John Redmond. The Party aimed at achieving Irish autonomy through constitutional means and managed to introduce the Home Rule Bill to the British House of Commons in 1912 to grant Home Rule to Ireland and give it a limited form of independence within the British Empire.

This caused fear in the predominantly unionist and protestant population in the northern province of Ulster. They feared losing their strong links with Britain and being governed by a catholic majority. In their perspective Home Rule would mean Rome Rule. As a consequence and led by Edward Carson, they established the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) in 1913 to resist Home Rule and fight against the rest of Ireland if needed. The nationalists responded by forming the Irish Volunteer Force (IVF) in the same year. Both UVF and IVF were openly military organisations that trained and drilled its forces and paraded them through the streets of cities and towns.

In Dublin, there was a second military force alongside the IVF that was also founded in 1913: The Irish Citizen Army (ICA). Led by James Connolly, it was the armed wing of striking workers during the Dublin Lock Out, the greatest labour dispute in Irish history. While small in size it was considered much better armed and disciplined than the IVF.

In 1914, Home Rule was to have been introduced. But it was suspended because of the outbreak of the First World War. As a result, both Carson and Redmond urged their respective volunteers to support the British army in the war effort. While a vast majority supported Redmond’s decision, a small group of nationalists opposed the Irish participation in the war. They also opposed the idea of Home Rule as they thought it didn’t go far enough. They wanted full independence from Britain.

There was another organisation that aimed at the same thing. Founded already back in 1858, the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) was dedicated to end British rule in Ireland and found an Irish Republic. The IRB’s primary maxim was:

England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity.

The fact that British troops were involved in the First World War was regarded as the perfect time to strike. Shortly after the war broke out, they established a Military Council and looked into the Irish Volunteer Force to undertake military action. The planning of the Rising was done by a small, radical group within the IRB. The main drivers were Thomas Clarke, Sean McDermott, Thomas MacDonagh, Patrick Pearse, Eamonn Ceannt, James Connolly and Joseph Plunkett. All of them were members of IRB’s Military Council. They should later sign the Proclamation of the Irish Republic.

Women also played an active role in the Rising. Many of them belonged to Cumann na mBan, an organisation formed in 1914 that was committed to using armed force against England. Their members trained themselves for fighting alongside the men.

Rising

The Rising was initially planned for Easter Sunday. The plans included a shipment of German weapons that was supposed to land on the Kerry coast on Good Friday. Unfortunately, the Royal Navy intercepted the Aud, the German vessel carrying the weapons. Its captain sunk his ship to avoid being captured. As a result, thousands of rifles were lost and the Rising was initially called off.

The more radical voices insisted to go ahead with the Rising and rescheduled it for the next day. They were aware that a rising under theses circumstances could not succeed. The late orders confused many volunteers causing them to miss the Rising. It surely wasn’t a smooth start.

Finally, on Monday 24 April 1916, the Rising began. Members of the Irish Volunteer Force, Irish Citizen Army, Irish Republican Brotherhood and Cumann na mBan marched down Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street) and took several buildings. They established the General Post Office (GPO) as their headquarters.

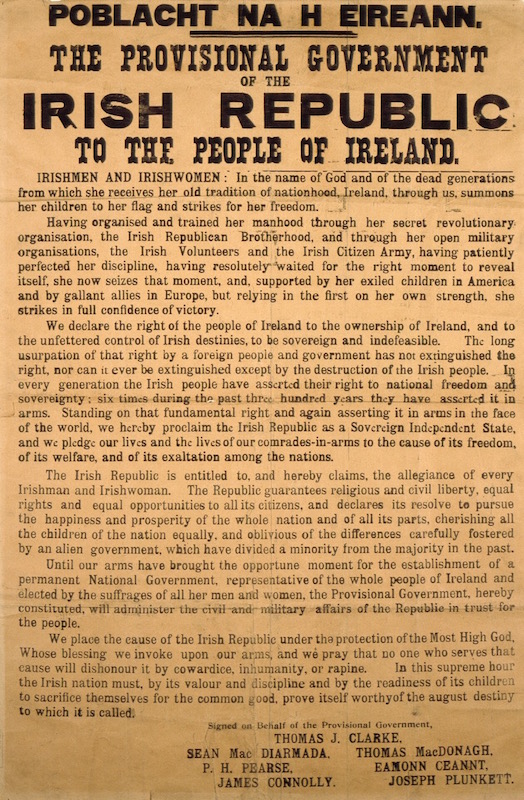

The Proclamation of the Irish Republic

Shortly after taking the GPO, Patrick Pearse appeared outside the building and read the newly composed Proclamation of the Irish Republic to a small gathering of onlookers. Although it outlined the establishment of an independent Irish Republic, the event passed largely without incident and the proclamation was met with amused indifference.

The proclamation combined the ideologies of the three key organisations that contributed to the Rising:

The document brings together the Republicanism of the Irish Volunteers with the socialism of the Irish Citizen Army and the feminism of Cumann na mBan.

– Professor Mike Cronin

The Proclamation of the Irish Republic surely is one of the most important documents in Irish history. Understandably, one of the main events during the official celebrations took place in front of the GPO when Captain Peter Kelleher of the Irish Defence Forces re-read the proclamation. His audience was definitely bigger and more alert than the one of Patrick Pearse 100 years ago.

Fighting

Shortly after the proclamation was read, the Brisith response began. A patrol was sent to Sackville Street and three battalions were ordered to defend Dublin Castle, the headquarters of the British administration. In addition to that, reinforcements were called to Dublin.

British troops began pouring into the city from all across Ireland and England. With thousands of soldiers in Dublin the main question was how long the rebels could resist. The rebel positions were immediately under siege. Heavy artillery rained down on them while they had to rely mainly on defending themselves rifle and sniper fire as well as with improvised explosives. The fighting was particularly fierce around Mount Street Bridge and North King Street. There, the death rate on both sides and amongst civilians was highest.

While the rebels were able to hold some buildings, there were others that quickly fell. The rebels were hampered by not succeeding at taking some key strategic sites. The failure to control railway stations and docks meant that the British could move troops into the city in large numbers relatively unimpeded. The failure to take Dublin Castle and Trinity College that was stocked with arms enabled the British to establish two important bases for their attacks.

Surrender and Executions

After profound artillery strikes on the city center, Patrick Pearse gave the order to surrender on Saturday, 29 April, to avoid further loss of civilian life and destruction of Dublin. The order to surrender read:

In order to prevent the further slaughter of Dublin citizens, and in the hope of saving the lives of our followers now surrounded and hopelessly outnumbered, the members of the Provisional Government present at headquarters have agreed to an unconditional surrender, and the commandants of the various districts in the City and County will order their commands to lay down arms.

It was over.

The fighting in Dublin lasted for six days killing almost 500 people and injuring several thousand. Civilians paid the highest price: They accounted for more than half of the deaths during Easter week. Half of the British casualties were the result of one battle at Mount Street Bridge, the bloodiest in the rebellion.

The high levels of artillery used by the British led to a huge number of fires around the Sackville Street area destroying numerous buildings. Before the Rising, Sackville Street was one of the finest streets in Europe. As the fighting concentrated in this area, the street was largely reduced to rubble by the end of the insurrection.

Many Irish viewed the rebels as traitors and insulted them as they were marched to their prison cells. 90 rebels were sentenced to death after the Rising. 15 of them including all the signatories of the proclamation were executed between 3 and 12 May by firing squad, 14 of them in Kilmainham Gaol. British authorities court-martialed around 170 of the over 3,200 rebels who were detained. Most of the prisoners interned abroad were sent back to Ireland in December 1916.

Legacy

The Easter Rising of 1916 marks the start of a new era in Irish history. Ireland surely wasn’t the same as it used to be.

Public opinion seemed to favour the British before and during the Rising, but it soon shifted in the aftermath. Stories of mass murder by British troops and unwarranted executions turned the Irish against the army.

– Joseph McCullough

When the Irish soldiers returned home from fighting in the First Word War, they were shunned by a changed society. Their involvement on behalf of the British was seen as a betrayal.

The impact of the Rising was huge and its legacy rather complex. Out of the many comments that I have read, I want to quote the following two to end this post.

The 1916 Rising was a seminal event led by men and women who held aspirations of a different type of Ireland, one which would guarantee religious and civil liberty and would pursue the happiness and prosperity of the whole nation, and all of its parts. It occurred at a time of conflict on the international stage, resulting in Irishmen losing their lives on the Western Front, Gallipoli, Mesopotamia, and at sea. The Rising resulted in the loss of many lives, be they combatants or innocent civilians. We commemorate these events on this their 100th anniversary and mourn the loss of all those who died.

– Department of the Taoiseach

The spirit of 1916, and the military lessons learnt from it, are central in understanding the Irish insurgency against Britain between 1919 and 1921 and the creation of an independent Irish Free State. […] Among the many questions still asked are whether the Rising was justified in light of the significant political achievements of the Irish Parliamentary Party and whether the Ireland of today is the one that the men and women of 1916 dreamed of.

– Professor Mike Cronin